Happy 300th Birthday Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706—April 17, 1790) was born in Boston, Massachusetts, to a tallow-maker. He became a newspaper editor, printer, merchant, and philanthropist in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was one of the most prominent of Founders and early political figures and statesmen of the United States. As a “self-made man” noted for his curiosity, ingenuity, generosity, and diversity of interests, he became an inspiration and model for many early Americans.

As a broad-minded thinker and political leader able to embrace all Americans, he was a source of unification of colonial society and the United States. As a philosopher and scientist, who had discovered electricity, he was at one point the most famous man in Europe. As a statesman in London before the Revolution, and Minister to France during the Revolution, he defined the new nation in the minds of Europe. His success in securing French military and financial aid, and recruiting military leaders in Europe was decisive for the American victory over Britain.

He published the famous Poor Richard’s Almanack and Pennsylvania Gazette. He organized the first public lending library and fire department in America, the Junto, a political discussion club, the American Philosophical Society, and public schools. His support for religion and morality was broad; he donated to all denominational churches (liberal and conservative) and the synagogue in Philadelphia.

He became a national hero in America when he convinced Parliament to repeal the hated Stamp Act. A diplomatic genius, Franklin was almost universally admired among the French as American minister to Paris, and was a major figure in the development of positive Franco-American relations. From 1775 to 1776, Franklin was Postmaster General under the Continental Congress and from 1785 to his death in 1790 was President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania.

Franklin was interested in science and technology, carrying out his famous electricity experiments and invented the Franklin stove, medical catheter, lightning rod, swimfins, glass harmonica, and bifocals. He also played a major role in establishing the higher education institutions that would become the Ivy League’s University of Pennsylvania and the Franklin and Marshall College. In addition, Franklin was a noted linguist, fluent in five languages, including Greek and Latin. Towards the end of his life, he became one of the most prominent early American abolitionists. Today Franklin is pictured on the U.S. $100 bill.

Early life

Benjamin Franklin was born on Milk Street in Boston, Massachusetts on January 17, 1706. His father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow chandler, a maker of candles and soap, who married twice. Josiah’s marriages produced 17 children; Benjamin was the tenth and youngest son. He attended Boston Latin School but did not graduate. His schooling ended at ten and at 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James, a printer who published the New England Courant, the first truly independent newspaper in the colonies.

Benjamin was an aspiring writer, but his brother would not publish anything he wrote. So, the apprentice wrote letters under the pseudonym of “Silence Dogood,” ostensibly a middle-aged widow. These letters became famous and increased circulation of the paper, but when James found out Ben was the author he became furious. Ben quit his apprenticeship without permission, becoming a fugitive under the law, so he fled from Massachusetts.

At the age of 17, Franklin ran away to Philadelphia, seeking a new start in a new city. When he first arrived he worked in several print shops. Franklin was noticed and induced by Pennsylvania Governor Sir William Keith to go to London, ostensibly to acquire the equipment necessary for establishing another newspaper in Philadelphia. Finding Keith’s promises of financial backing a newspaper to be empty, Franklin was stranded in England, so he worked as a compositor in a printer’s shop in Smithfield. With some savings with the help of a merchant named Thomas Denham, who gave Franklin a position as clerk, shopkeeper, and bookkeeper in his merchant business, Franklin returned to Philadelphia in 1726.

Upon Denham’s death, Franklin returned to his former trade. By 1730, Franklin had set up his own printing house with the help of a financial backer and became the publisher of a newspaper called The Pennsylvania Gazette. The Gazette gave Franklin a forum to write about a variety of local reforms and initiatives. His commentary, industriousness, personal growth, and financial success earned him great social respect at a very young age.

Civic Virtue

Franklin strongly promoted the idea of civic virtue and strove to be an exemplary leader. Franklin was an avid reader, self-taught in several languages and fluent in the classics. He read and conversed with Enlightenment thinkers in England, and became a leader of the Freemasons in Philadelphia, who promoted public service, erection of large public buildings, and religious tolerance. He also founded the American Philosophical Association.

Franklin and several other local leaders joined their resources in 1731 and began the first public library in Philadelphia, inventing the concept of lending books and library cards. The newly founded Library Company ordered its first books in 1732, mostly theological and educational tomes, but by 1741 the library included works on history, geography, poetry, exploration, and science. The success of this library encouraged the opening of libraries in other American cities.

In 1733, he began to publish the famous Poor Richard’s Almanack (with content both original and borrowed) on which much of his popular reputation is based. His own views on self-discipline and industriousness were promoted in adages from this almanac such as”A penny saved is twopence clear” (often misquoted as “A penny saved is a penny earned”), “The early bird gets the worm,” and “Fish and visitors stink after three days” remain common quotations in the modern world. He sold about ten thousand copies a In 1736 he created the Union Fire Company, the first volunteer firefighting company in America. In 1743, he set forth ideas for The Academy and College of Philadelphia. He was appointed President of the Academy in November 13 1749, and it opened on August 13 1751. At its first commencement, on May 17, 1757, seven men graduated; six with a Bachelor of Arts and one as Master of Arts. It was later merged with the University of the State of Pennsylvania, to become the University of Pennsylvania, today a member of the Ivy League.

In 1751, Franklin and Dr. Thomas Bond obtained a charter from the Pennsylvania legislature to establish a hospital. Pennsylvania Hospital was the first hospital in what was to become the United States of America.

Religious Toleration

Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn who was know for his insistence on religious toleration. Philadelphia was known as a city where every type of belief, church, and sect flourished. Franklin was a great promoter of religious toleration and worked to create a city, and later a national culture, where people of all religious and cultural backgrounds could live together in harmony.

Franklin worked out his own moral code and belief system at an early age and it evolved with his experience. He was called a Deist because he was a free thinker who did not take the miracles in the Bible literally. However, unlike the deists who viewed God as the “clockmaker” who wound up the universe and left, Franklin believed in God’s active Providence in human affairs.

Franklin believed that all religions helped to fortify the personal self-discipline and morality required for self-governance and democracy. He told his daughter Sarah to attend church every Sunday, but that he didn’t care which one she chose to attend. At one time or another Franklin gave money to every church in Philadelphia. He owned a pew in the Episcopal Church, he built a church for evangelist George Whitfield when he came to Philadelphia, and he contributed the the building of the first Jewish synagogue. Such generosity and tolerance earned Franklin many friends and a reputation for having a big mind and heart that could transcend the petty bickering so common in human affairs and make him a successful politician who earned the respect and could represent the interests of all Americans.

Scientific Inquiry

Inspired by the scientific discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton and other European contemporaries, Franklin engaged in scientific inquiries when not heavily occupied by money-making or politics.

In 1748, he retired from printing and went into other businesses. He created a partnership with his foreman, David Hill, which provided Franklin with half of the shop’s profits for 18 years. This lucrative business arrangement provided leisure time for study, and in a few years he had made discoveries that made him famous throughout Europe, especially in France.

Electricity

These include his investigations of electricity. Franklin proposed that “vitreous” and “resinous” electricity were not different types of “electrical fluid” (as electricity was called then), but the same electrical fluid under different pressures (See electrical charge). He is also often credited with labeling them as positive and negative respectively. In 1750, he published a proposal for an experiment to prove that lightning is electricity by flying a kite in a storm that appeared capable of becoming a lightning storm. On May 10, 1752, Thomas Francois d’Alibard of France conducted Franklin’s experiment (using a 40-foot-tall iron rod instead of a kite) and extracted electrical sparks from a cloud. On June 15, Franklin conducted his famous kite experiment and also successfully extracted sparks from a cloud (unaware that d’Alibard had already done so, 36 days earlier). Franklin’s experiment was not written up until Joseph Priestley’s 1767 History and Present Status of Electricity; the evidence shows that Franklin was insulated (not in a conducting path, as he would have been in danger of electrocution in the event of a lightning strike). (Others, such as Prof. Georg Wilhelm Richmann of St. Petersburg, Russia, were spectacularly electrocuted during the months following Franklin’s experiment.) In his writings, Franklin indicates that he was aware of the dangers and offered alternative ways to demonstrate that lightning was electrical, as shown by his invention of the lightning rod, an application of the use of electrical ground. If Franklin did perform this experiment, he did not do it in the way that is often described (as it would have been dramatic but fatal). Instead he used the kite to collect some electric charge from a storm cloud, which implied that lightning was electrical. See, for example, the 1805 painting by Benjamin West of Benjamin Franklin drawing electricity from the sky.

In recognition of his work with electricity, Franklin was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and received its Copley Medal in 1753. The cgs unit of electric charge has been named after him: one franklin (Fr) is equal to one statcoulomb.

Meteorology

Franklin established two major fields of physical science, electricity and meteorology. In his classic work (A History of The Theories of Electricity & Aether), Sir Edmund Whittaker (p. 46) refers to Franklin’s inference that electric charge is not created by rubbing substances, but only transferred, so that “the total quantity in any insulated system is invariable.” This assertion is known as the “principle of conservation of charge.”

As a printer and a publisher of a newspaper, Franklin frequented the farmers’ markets in Philadelphia to gather news. One day Franklin inferred that reports of a storm elsewhere in Pennsylvania must be the storm that visited the Philadelphia area in recent days. This initiated the notion that some storms travel, eventually leading to the synoptic charts of dynamic meteorology, replacing sole dependence upon the charts of climatology.

Other Science and Accomplishments

Franklin noted a principle of refrigeration by observing that on a very hot day, he stayed cooler in a wet shirt in a breeze than he did in a dry one. To understand this phenomenon more clearly Franklin conducted experiments. On one warm day in Cambridge England in 1758, Franklin and fellow scientist John Hadley experimented by continually wetting the ball of a mercury thermometer with ether and using bellows to evaporate the ether. With each subsequent evaporation, the thermometer read a lower temperature, eventually reaching 7° F (-14 °C). Another thermometer showed the room temperature to be constant at 65 °F (18 °C). In his letter “Cooling by Evaporation,” Franklin noted that “one may see the possibility of freezing a man to death on a warm summer’s day.”

His other inventions include the Franklin stove, medical catheter, lightning rod, swimfins, the glass harmonica, and bifocals.

In 1756, Franklin became a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures & Commerce (now Royal Society of Arts or RSA, which had been founded in 1754), whose early meetings took place in coffee shops in London’s Covent Garden district, close to Franklin’s main residence in Craven Street (the only one of his residences to survive and which is currently undergoing renovation and conversion to a Franklin museum). After his return to America, Franklin became the Society’s Corresponding Member and remained closely connected with the Society. The RSA instituted a Benjamin Franklin Medal in 1956 to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Franklin’s birth and the 200th anniversary of his membership of the RSA.

During a trip to England in 1757, Franklin was awarded an honorary doctorate for his scientific accomplishments by Oxford University, and from then on went by “Doctor Franklin.”

In 1758, the year in which he ceased writing for the Almanac, he printed “Father Abraham’s Sermon,” one of the most famous pieces of literature produced in Colonial America.

While living in London in 1768, he developed a Phonetic alphabet in A Scheme for a new Alphabet and a Reformed Mode of Spelling. This reformed alphabet discarded six letters Franklin regarded as redundant, and substituted six new letters for sounds he felt lacked letters of their own; however, his new alphabet never caught on and he eventually lost interest.

Political Leadership

This political cartoon by Franklin urged the colonies to join together during the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War).In politics Franklin was very able, both as an administrator and as a diplomat. His most notable service in domestic politics was his reform of the postal system, but his fame as a statesman rests chiefly on his diplomatic services in connection with the relations of the colonies with Great Britain, and later with France.

In 1754 he headed the Pennsylvania delegation to the Albany Congress. This meeting of several colonies had been requested by the Board of Trade in England to improve relations with the Indians and defense against the French. Franklin proposed a broad Plan of Union for the colonies, The United Colonies of America. While the plan was not adopted, elements of it found their way into the Articles of Confederation and later the Constitution. Franklin’s newspaper, which was distributed throughout the colonies, was instrumental in creating a national identity before the American Revolution.

In 1757 Franklin was sent to England to protest against the influence of the Penn family in the government of Pennsylvania, and for five years he remained there, striving to enlighten the people and the ministry of the United Kingdom about colonial conditions. He also managed to secure a post for his son, William Franklin, as Colonial Governor of New Jersey.

On his return to America (1762), Franklin played an honorable part in the Paxton affair, through which he lost his seat in the Assembly. But in 1764, he was again dispatched to England as agent for the colony, this time to petition the King to resume the government from the hands of the proprietors.

Revolutionary times

In London, he actively opposed the proposed Stamp Act, but lost the credit for this and much of his popularity because he had secured for a friend the office of stamp agent in America. This perceived conflict of interest, and the resulting outcry, is widely regarded as a deciding factor in Franklin’s never achieving higher elected office. Even his effective work in helping to obtain the repeal of the act did not increase his popularity, but he continued to present the case for the Colonies as the troubles escalated toward the crisis which would result in the Revolution. This also led to an irreconcilable conflict with his son, who remained ardently loyal to the British Government.

In 1773 or 1774 Thomas Paine visited Franklin in England and enthusiastically discussed his book manuscript critical of many religious doctrines. Franklin, while personally agreeing that many of the miracles in the Bible were unbelievable, argued that the moral teachings in the Bible were the highest teachings known, and to undermine them without providing a better replacement would ruin personal character and destroy society. Franklin told Paine to burn the manuscript, but he sent Paine back to America full of ideas about an independent United States.

Before his return home in 1775, he lost his position as postmaster and broke with England after leaking information about Thomas Hutchinson, the English-appointed governor of Massachusetts. Although Hutchinson pretended to take the side of the people of Massachusetts in their complaints against England, he was actually still working for the King. Franklin acquired letters in which Hutchinson called for “an abridgment Liberties” in America and sent them to America causing outrage. Franklin was called to Whitehall, the English Foreign Ministry, where he was condemned in public.

In December of 1776, he was dispatched to France as commissioner for the United States. He lived in a home in the Parisian suburb of Passy donated by Jacques-Donatien Le Ray de Chaumont who would become a friend and the most important foreigner to help the United States win the War of Independence. Franklin secured the support of the King of France for the American Revolution and recruited military leaders to train and lead soldiers.

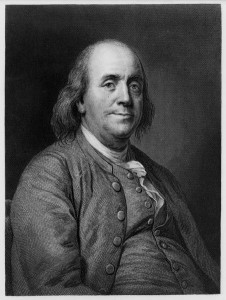

Franklin remained in France until 1785, and was such a favorite of French society that it became fashionable for wealthy French families to decorate their parlors with a painting of him. He conducted the affairs of his country towards that nation with great success, including securing a critical military alliance and negotiating the Treaty of Paris (1783). When he finally returned home in 1785, he received a place only second to that of George Washington as the champion of American independence. Le Ray honored him with a commissioned portrait painted by Joseph Siffred Duplessis that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC.

Last Years

After his return from France, Franklin became an ardent abolitionist, freeing both of his slaves. He eventually became president of The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.

In 1787, while in retirement, he was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention that would produce the United States Constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation. It met in Pennsylvania under the leadership of George Washington, who struggled to guide the discussion above the petty and selfish interests of the states and delegates. At one point discussions broke down and Hamilton went home. Progress remained elusive until wise elder statesman Franklin stood up and gave a prescient speech in which he stated that creation of the Constitution was a unique opportunity for a people to create a government based on reason and goodness, not the will and power of a military conquerer. He pleaded for humility and recommended the Convention begin each day with prayer to orient them to a higher purpose. This speech marks the turning point for drafting the Constitution.

He is the only Founding Father who is a signatory of all three of the major documents of the founding of the United States: The Declaration of Independence, The Treaty of Paris and the United States Constitution. Franklin also has the distinction of being the oldest signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. He was 70 years old when he signed the Declaration, and 81 when he signed the Constitution.

Between 1771 and 1788, he finished his autobiography. While it was at first addressed to his son, it was later completed for the benefit of mankind at the request of a friend.

In his later years, as Congress was forced to deal with the issue of slavery, Franklin wrote several essays that attempted to convince his readers of the importance of the abolition of slavery and of the integration of Africans into American society.

On February 11, 1790, Quakers from New York and Pennsylvania presented their petition for abolition. Their argument against slavery was backed by the Pennsylvania Abolitionist Society and its president, Benjamin Franklin. Because of his involvement in abolition, its cause was greatly debated around the states, especially in the House of Representatives.

Legacy

Benjamin Franklin died on April 17, 1790 at the age of 84. 20,000 people attended the funeral. He was interred in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

At his death, Franklin bequeathed £1000 (about $4400 at the time) each to the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, in trust for 200 years. The origin of the trust began in 1785 when a French mathematician named Charles-Joseph Mathon de la Cour wrote a parody of Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack called Fortunate Richard. In it he mocked the unbearable spirit of American optimism represented by Franklin. The Frenchman wrote a piece about Fortunate Richard leaving a small sum of money in his will to be used only after it had collected interest for 500 years. Franklin, who was 79 years old at the time, wrote back to the Frenchman, thanking him for a great idea and telling him that he had decided to leave a bequest of 1,000 pounds each to his native Boston and his adopted Philadelphia, on the condition that it be placed in a fund that would gather interest over a period of 200 years. In 1990, over $2,000,000 had accumulated in Franklin’s Philadelphia trust. During the lifetime of the trust, Philadelphia used it for a variety of loan programs to local residents. From 1940 to 1990, the money was used mostly for mortgage loans. When the trust came due, Philadelphia decided to spend it on scholarships for local high school students. Franklin’s Boston trust fund accumulated almost $5,000,000 during that same time, and eventually was used to establish a trade school that, over time, became the Franklin Institute of Boston. (excerpt from Philadelphia Inquirer article by Clark De Leon)

*This article is taken from the New World Encyclopedia, which is developing a value-oriented encyclopedia based on Wikipedia. The orginal Wikipedia article was rewritten by Gordon L. Anderson for the Encyclopedia Project, which be released in 2008.

Comments

Happy 300th Birthday Benjamin Franklin — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>