Interview with Interfaith Veteran, Robyn LeBron-Anders: “Do You Think We Will Ever Get It Right?”

This is an especially good interview for anyone interested in Interfaith either personally or professionally. It contains valuable information for everyone from first time beginners, to seasoned interfaith veterans

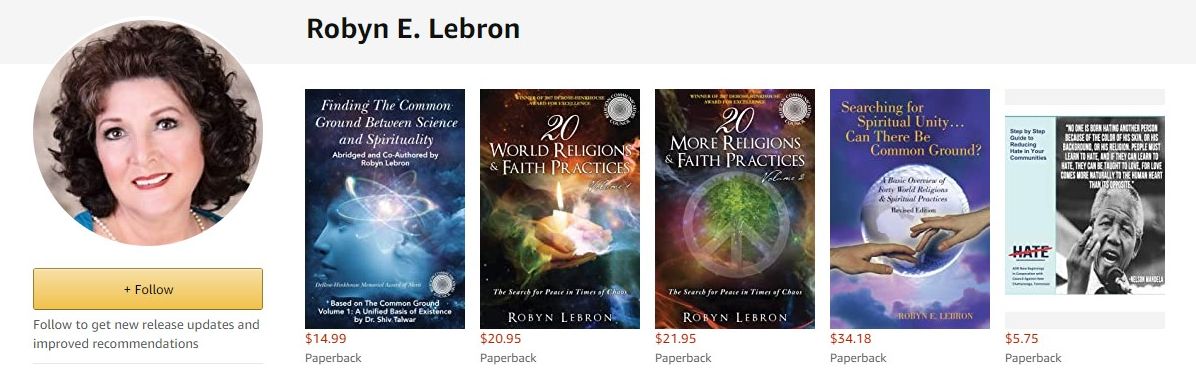

Robyn E. Lebron

Writes in the arena of World Religion. Her books received the 2018 Best in class DeRose-Hinkhouse Memorial Award for Excellence in Religious Communication, given annually by Religion Communicators Council.

Her book “Finding Common Ground between Science and Spiritually” was awarded the DeRose-Hinkhouse Award of Merit in 2019.

She also was recognized internationally by The Books For Peace Commission 2019 for those who have distinguished themselves in the activities of peace and solidarity.

Ms Lebron manages Interfaith Professionals on LinkedIn, with over 5,400 members, has written articles for United Religions Initiative, Harmony Interfaith Initiative, The Interfaith Observer.

See the image and links to Robyn’s books and writing, and if you like, read the rough transcript of this important conversation here

Please visit Robyn’s Amazon page here

Robyn Anders Transcript

Good morning, I’m Frank Kaufmann, President of Twelve Gates Foundation. We’re excited to have with us today on the program. Robyn LeBron, or Robyn Lebron Anders. Robyn writes in the area of world religion. Her books received the 2018 best in class DeRose-Hinkhouse Memorial Award for Excellence in religious communication that’s given annually by the Religion Communicators Council. Her book, Finding Common Ground between Science and Spirituality was awarded the DeRose-Hinkhouse Award of Merit in 2019. She was also recognized internationally by the Books for Peace Commission in 2019. For those who have distinguished themselves in the activities of peace and solidarity. Ms Lebrun manages interfaith professionals on LinkedIn, which has over 5400 members. She writes articles for the United Religions Initiative. Harmony interfaith initiative. The interfaith observer, and many other outlets for writing in the field of religion and interfaith. Please join me to welcome to the program. Ms. Robyn Lebron.

Robyn Hello, can you hear me fine?

Hello,

Welcome. Glad to have you.

Yes I can hear you.

Oh, that’s great, that’s great.

Thank you so much for having me.

Oh, it’s my pleasure, I’ve looked forward to this for a long time. And this is a great opportunity because you’ve just released a piece of a little bit of writing, and I think you’re causing a stir already with it. The name of the piece is called, Do You Think We’ll Ever Get It Right, and the subtitle or kind of a tagline says “a tiny book with a huge message.” And I think this little book already stirred the waters up pretty turbulently. Well, we’ll get into that in a second. I just wanted the listeners to know about the fact that you don’t write only little tiny books. Sometimes you write very big books, When they read Will We Ever Get It Right, they’ll come across your brief mention of a prior work that I think is probably the main thing you’ve created in print. Can you say a word or two about that effort.

Yes. My first book was a reference manual to 40 world religions and faith practices. And you’re right it is huge, and in fact it was so huge that I thought it was daunting to a lot of people. So I broke it into two volumes. Now, they’re called 20 World Religions and Faith Practices, and the second volume is 20 More World Religions and Faith Practices and my purpose is to share the beauty in the teachings. The core Golden Rule teachings in all these world religions, so that we could grow closer together.

Very good. Very good. Most people don’t think of the world’s religions as 40. How did 40 come to be the focus of your effort there.

Well some of them are denominations, so that’s why I said religions and faith practices. It was designed as a teaching tool to open people’s minds about the current faith practices out there. The first 20 were chosen by the number of members in the world largest communities,

Yeah we actually taught a course, and it took us a year to get through those. And after that was done, they said oh we want more we want more so the second 20 was based on faith practices that are misunderstood. Very unusual. You know, to give you a whole different kind of spin on World Religions of faith practices.

Excellent. So this original book with the two volumes with 20 practices in each of the two volumes. This was originally taught to a study group in a Christian congregation or where was it taught?

Yes it was. I was married to a pastor, and I was trying to open the congregation’s worldview. And so it was an Episcopal Church, and we taught it once a week for two years, basically. Very good.

I spent a long many years of my church attendance in an Episcopal Church and I think that generally speaking among the denominations it’s, it might be one of the better Christian denominations in terms of openness and curiosity and willingness to learn and not to narrow visa V overreaction against or or fearful of other religious learning. Was that your experience also.

Sorry to disagree.

Then you will have something to offset.

Okay, so maybe it’s just east “coastness” rather than “Episcopalianness.” Alright,

well, perhaps the congregation was very old. And so there were a lot of people which I will fondly call the Old Guard, and they really didn’t want anything changed, and you know they weren’t as open to the new ideas that would appeal to young families and you know it was just the way it was, you know, so I dealt with it. And unfortunately the courses we taught the people that attended were not the ones that needed to attend. In other words, we were preaching to the choir.

Okay, okay. Yeah, I get it. Very interesting. Of course my congregation too had a lot of elderly. I think maybe New Yorkers, I don’t know maybe urban people, I don’t know but they just, they just keep learning, They never stop learning. That’s the big thing in cities I think is just keep learning and learning, but good. I’m getting on to getting on to this work because you, you do trace that you even mentioned your experience with your congregation there as part of, part of the trajectory and of course of your interfaith experience and what’s bringing you to this set of very serious challenges in this work. Will We Ever Get It Right. And, as, as a person who has a lifelong investment in a religious life and interfaith pursuits and part of part of your writing here is the challenges even of that itself, and the kind of parochial elements that creep into even interfaith as an enterprise, and your significant your significant in the field. You’ve been prominent. When I joined the, the interfaith professional LinkedIn group, you’re that you’re the head of it, you were the head of it, or are.

I manage it, yes.

Yeah, and in your book you mentioned it existed you joined it at one point, is that correct it existed already. And then you joined it Yes,

Yeah, I joined it in 2013 and there were about 900 members, the gentleman who started it was a kind of a computer geek. Yeah. And, um, you know I was just all of a sudden he reached out to me and he’d been reading my posts, obviously, and he said I want you to manage the group. I just don’t have time. And, you know, there was like 100 membership requests that he hadn’t dealt with and so yeah I just kind of hit the ground running and, and I’ve been doing it ever since.

You’re humble because under your management it rose from 900 to 5400 presently in that group. Yes. That’s an incredible platform and incredible voice. And, a big responsibility. I know that membership in groups with Facebook or LinkedIn there isn’t the hot commitment but still the ideals have to have to unfold somewhere and that’s another huge work of yours. But what I was about to start with my first question is that almost all people in the field, you know, there’s the big names, there’s the Vendleys, the Swings, Robert Morton of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in northern Manhattan. There’s always a story, there’s always an autobiographical element that is part of the roots of that particular individual, who becomes or rises up to become an interfaith known interfaith name and figure. And I think you must also, there must also be that in your own life and narrative in your upbringing or how you were raised religiously in your household or how do you how do you come by that, how do you come by that you’ve that this became such a passion of yours.

Well, I was raised in the Air Force, so we traveled a lot, I met lots of different people, different religions, different races, you know, and children are very open, you know you don’t meet a child on the playground and say What religion are you, and so I approach life with a childlike openness, and I was not taught any differently, as I experienced different organized religions, I found myself frustrated that they kept trying to you know create dividers between people and that was just not my understanding of God never has been. And so, the older I got, the more I realized that we really need to learn to love each other like the Bible tells us to, and how can I go about helping that happen.

Okay, or your parents did they raise you in a church, or not at all.

No, my mom was, you know, she was very strong in her belief of God in fact she was an orphan. And she told me when she was a little girl, she’d go to her, her sort of secret place, and she’d sit on the rock and she’d have arguments with God about why she was going through this, you know, and she was little and she still believed in God even everything when she was going through, but because we traveled around so much. There wasn’t always a specific denomination available, close to where we lived, so we went to lots of different ones and that may have played into it as well.

Okay. Okay, so, so your parents, they were believers, but the constant movement didn’t really allow a fixed bond to a single denominational identity. So you grew up in the presence of faith and of faithfulness and of appreciation of religious life, but not such that, it was narrowly identified with a kind of a constant and unchanging membership or named identity, something like that is that. Does that sound right?

Exactly, exactly.

So that sets you up to be naturally affirmative and have faith as a thing. And trust that it’s in lots of places in order to bring a listener into what this conversation is, is genuinely about your book. Will We Ever Get It Right. Is it fair for me to say that. To sum it up. Sentence 1: sInterfaith activity can itself become just like being a member of a religion itself, and Sentence 2: To the extent that interfaith interfaith membership or interfaith identity becomes like that. Then, then the whole enterprise starts to decline from its capacity to bring about the growing harmony and cooperation that, by nature, it should define itself as promoting. Does that sound like some of the thread that runs through this book, How Will We Ever Get It Right.

Yes, exactly. I mean I’ve met so many lovely people in the interfaith movement, but as soon as you start putting walls up and saying you know we’re more advanced or we’re more spiritual or we’re more we’re the newest flavor of the month and then you’ve created another division, and it defeats the whole purpose. So, I mean that has kind of made me sad.

And so, and you’ve invested almost your whole life, as you just described in huge ways to accomplish huge things like quadrupled or quintupled the membership of, of a vibrant interfaith LinkedIn group you’ve created a review of of 40 faith traditions in which you labored through even resistance to try to make those appealing and known, and then you come to a juncture in, in your career or history, which suddenly you see that the very enterprise itself starts to calcify and starts to imitate or emulate the very reality about religious life, that it was meant to address a couple of things occurred to me as I read is that you have a string of very sweet and very fond recollections and accounts of significant saintly and Premiere individuals who have had an impact on your life. It starts out with an elderly Mormon missionary correct and I’m correct, yes,

yes, actually she was a young woman she was probably about 25 But she was very frail, and just, you know, the closest I’ve come to ever meeting an angel on the earth.

And then as the course of your interfaith efforts in life progressed, you continue to meet exceptional individuals who embody the ideals and the virtues that should be the definition of the work itself. Right, you mentioned a handful of people along the way.

Yes, absolutely.

And then simultaneously throughout the book so we meet these fine people, and it’s exciting to meet them on the pages of your writing. We feel drawn to them, even though we may never have met them. And at the same time, it seems you’re traveling through a string of institutions, all of which disappoint you. So there’s a constant flow of individuals, which inspire you, there’s plenty that disappoint you no doubt, but, there’s a constant string of individuals who inspire you and these constant institutions which disappoint you. I don’t know if you saw it that way but this a little bit how it read to me. So, in that Episcopal Church mentioned in your book, after you spent three or four years there killing yourself. Somebody says, to you, do you think you’re ever going to join right or something like that, isn’t that in your book. Yeah, yeah, so, institution after institution, and then you go through, I know you’ve been through the whole nine in the, in the professional interfaith world the Parliament of the World’s Religions, NAIN which stands for North American Interfaith Network, and you’ve been through, you know, naturally in your field, you’ve been through all the big names and all the big activities and all the big meetings and. And now these themselves are starting to line up behind the institutional disappointment, along the way. So what I wanted to kind of ask you to ponder, or speak on is, is it institutions per se that where the problem lies not interfaith but even if we were going to make a little sandlot baseball club. As soon as we buy uniforms and have to sign up, then that’s gonna, you know, is it, is it the institutionalization of that is that the problem, so that you know you’re going to meet some young mom who’s going to toss underhand, get on a team or something who knows you’re going to need saints, along the way and everything, and is it is it just institutionalization that is going to sooner or later be harder, harder to manage. Because the reason I asked that is because, then, then the religions themselves also. That’s, that would also be their problem. It’s not that. It’s not that. Do you see what I’m saying is that, is that the problem that, that you never found an institution.

Yes. Well, not exactly, I’ll tell you what I was trying to get across in my book, is that the messages, you know, the beautiful messages within the faith practices are there. Regardless, and there are beautiful people within the faith practices that are also there. But unfortunately, a sort of laziness and mediocracy and stuff like that has worked in. So there’s those out there that are going to disappoint and a person can’t hang their faith on these individuals that are not carrying the torch properly. That is one message that you have to find your own faith and your own anchor and not judge a faith by somebody who’s in it. Number one. Number two, I also found some exceptional individuals that were kind, loving, open, but they all had these unconscious lines in the sand, that they were not aware of that. They could be open and loving and caring for everybody but some one exception to their lofty embrace. Right. And, you know, and it was kind of surprising, surprising to me to see that happen so many times. Yes, and so that’s another thing I was trying to make people aware of is do you have a line in the sand that’s keeping you from being totally open. And that was one of the things that started to bother me about the interfaith groups is that their lines in the sand are not even unconscious, I mean they’re blatant in some cases, when I was at the main conference. I heard people saying really rude things about Scientology. Scientology is in my book. Yeah and so I’ve researched it and you know it’s not my cup of tea, but it’s above my paygrade to judge them and to say rude things about him in public at an interfaith activity. I mean to me that is the absolute antithesis of interfaith. And so, you know, that made me sad that people are saying they want to be involved in they’re nice people I’ve met lots of nice people, but they just aren’t aware that they are nice to everybody except some certain small group that they don’t like for whatever reason, whether it’s a life experience or lack of knowledge, you know, my little chapter on going through life with a flashlight, I mean that tries to discuss how people see what they see, you can’t help what they see, they only have this small circle of light and that’s how they’re judging everything. I hope that makes sense.

Yeah, that’s tremendous. That’s very helpful. By going into the kind of, I won’t call it the Belly of the Beast maybe the center of the flame that the lightest, the lightest part you can find, which is those people who are dying to love everybody there in the interfaith movement itself, going to the best place you can find they’re spending $1,000 to fly to Melbourne or here or there, they think their whole self definition is loving everybody they can find and then you walk by someone in a coffee break who’s taking it out on some religion, the one they, they refuse access to this big breadth that they pursue in their life. And I wonder if you’ve identified something that’s simply in human nature, that would call for an inquiry into what makes that problem if everybody is prone to have a line in the sand, even the cleanup batter, you know the head of, you name the organization you, and then you find out that he or she has this little secret group they hate, then you might be talking about something that is common to human nature. And then, would the interface or interface enterprise, be responsible to come up with what addresses that. So, possibly being a Baptist, that it doesn’t assign itself the mission for people not to have lines in the sand, possibly, possibly being a Baptist having lines in the sand is no big problem, but to NAIN or to be in the World Parliament, having lines in the sand should technically be a problem. So if those groups are they the ones responsible for this problem you shouldn’t have, wouldn’t they be responsible to come up with regimens or practices for that particular thing that is found in all human beings. Let the Baptists worry about not stealing and not coveting thy neighbor’s wife and, and maybe the interfaith people can come up with what to do about our lines and sand,

Yeah, well I, I don’t think a lot of people realize they have one, I think that’s the problem. Like I said some of these people are just really really nice people. And just as a kind of a quick example on Academia, there’s been a conversation about this little book, and there was a guy who kept making comments about God and why am I bringing God into it if I’m trying to fix everything and blah blah blah, and I finally said, Well, you know, it’s quite obvious to me that you have an unconscious line in the sand about any confirmation or conversation that includes a Supreme Being. And then he replied, He said, Well, I wasn’t aware of any line in the sand but then he admitted that he was an agnostic. So, although he was trying to be his, his comments weren’t rude he was trying to be constructive. but he had a line in the sand that he hadn’t really thought about, you know, and I think that’s part of the problem and that’s one of the reasons why I wanted to do this, to help people see. You know you can be a really nice kind loving person and not realize that it only goes so far and for us to really have peace we have to find those lines in the sand and erase them.

That’s a great statement and a great work, even just to shine a light there, because the interfaith movement has been around for a long time. Now it’s getting quite old, and there’s a lot to critique about it but it still holds a bright appeal to too many who are just learning the, the joys of openness and learning about new traditions so it’s still serving a very good part on its on its outer frontier, but deep on the inside, how its veterans are going to be vigilant about ourselves and about our biases, is a great point. We’re bringing into a group and you speak with the authority to do so because you’ve invested so constantly in that world, we’re almost gonna wrap up. But I was wondering if, before we do on this matter of addressing our shortcomings or, or where our openness closes down. What about the areas that are really problematic, where we’re somehow compelled or obliged to in fact be hostile to things that was the way I wrote it in my notes for question was, no matter how broad you define yourself, there’s going to be somebody that’s going to stand outside of your minimal version of your BASIC virtues and demand that you accept them to. Do you get what I’m saying? Y say, well, we can all agree, yeah. Okay, you got the question, what do you think about that paradox of. Yes, I accept everybody but I really somehow child sacrifice. I can’t quite bring myself around to wanting them at my conference. It has to do with the question of difference versus good and evil, I was wondering if you had any kind of thoughts or reflections about this.

Well that’s, that’s actually a very difficult question because, you know, if you just talk about can we have universal morality and, you know, not judge and try and love our neighbor as ourselves and but you’re right, there are some people that have a different sense of morality, and for whatever reason they think a certain action is okay because that’s what they’ve been taught, and we think, oh no this is absolutely not okay and I have to draw my line in the sand there, so I don’t know how you solve that problem because you’re right, there are people that have completely different upbringings and completely different cultures and that all comes into it as well. But, you know, part of the problem is that chapter on letting God be God.

Yes.

I mean, if I saw somebody that was child sacrificing I would call the police. But I wouldn’t personally, you know, do anything to them, it’s not, it’s again it’s above my paygrade. So, In some cases you. You do what you can, if you see evil being done as another person being hurt. We definitely, you know, if we are moral then we’re gonna stand up and defend somebody who’s being hurt, that’s my definition of morality, I agree, I know what you’re saying. It is difficult, but you have to, yeah, you have to let God work out some of these things. Because.

Right, right. It’s a real challenge, and it should be a constant point of conversation and should be worked out in a serious and sophisticated ways, giving the conversation all the time it needs to be had. Perhaps these types of things are part of what should be the, the nature of interfaith meetings, is the hard questions. The question of evil, I mean traditionally religions have positions visa vis evil, whereas the stance of acceptance is always challenged by the concept of that which is unacceptable by any measure, and I think you’ve taken a first step with this, let God be God. And having distinct ways of dealing with things that don’t require your violation of your desire to level people, it’s good stuff. One of the things that comes up in your book is the parts of the interfaith community that have, like you mentioned this fellow and the in the academia group, that the mere mention of God is becoming too narrow or to an inner religious conversation. And so you mentioned a session at the parliament that you recently attended, I guess must have been in Toronto, I think, right, what was it, what was the name of that session,

it was in Toronto, and well I can’t remember the exact name but it was something like, Is God dead or is there a God, something along those lines.

Yeah, and this was a surprise to you what the popularity of the session or that it did. Can you speak about that kind of direct certain directions in which you get interfaith to such an extent that having any religious belief at all becomes the wrong thing to do.

Yeah, I mean that is definitely a problem when you say well you have to accept Scientology then I can’t very well go and say well you can’t accept Satanism, and although, you know, that’s what I feel. But the problem that I find is that the more Heneral taking God and faith out of the movement seems to be a direction that they’re going, as though you have to take God out to be totally inclusive. Yeah, and you know that breaks my heart because no the religions aren’t perfect and yes, there’s been many religions that had horrific times in their history, but they were brought on by zealots, but in general the teachings of the different faith practices are beautiful, I mean the message God has given our profits over the centuries is unbelievable, even traditional African religion it’s like 50,000 years old, they got the same message from God. So the message is good, but humans have just kind of messed with it too much and I’m afraid that’s what’s happening to interfaith as well, that humans are getting in and they’re stirring the pot too much, and affecting the effectiveness affects the effectiveness, if that makes sense.

Yeah.

Is there emerging in the interfaith community and kind of a roster of good guys and bad guys like, It’s wonderful to love every, every bang on the log of the Yoruba religion but God forbid you should ever think the Pope or Catholic views are OK. Is there any of that in your experience that somehow the mainstream conventional every day groups, say an evangelical believer who loves his country and they’re not the big popular ones at the chapel across the street from the UN and so forth is there a certain type of religious group that oddly, it’s the mainstream religions that have a greater trouble finding acceptance in the broad interfaith community is that at all the case or not so not in your experience,

I think it is, I think that more conservative faith practices are struggling in fact, A couple years ago, there was an article written and I can’t remember who off the top of my head wrote it, but it was called, you know who’s missing from the table. And it was quite openly talking about how evangelical Christians were not even invited. And if they did show up like at that name conference I had a real young conservative Christian come up to me after my comment, and thank me because he never really truly felt embraced or included. And so they’re not including the ones that are fashionable almost and that’s a bad sign to me.

Yeah, well I think you’ve really hit it in a neutral and loving way, that we all have our blind spots we all have our lines in the sand. No one is deliberately trying to be a bad person. And, if only our community, the interfaith community could start to acknowledge that and then start to take it seriously and start to look at ways that we can address it and get better and overcome it. What do you think?

Well I had hoped that this would make some people, both interfaith and non interfaith people think and ponder and, you know, kind of think about it you know am I doing this unconsciously, interestingly enough, I’ve sent my little book to several people to read it and comment on it, and some agreed with me but they were afraid to come out of the closet and say they agreed with me, you know, because it how it would affect their their position in the interfaith movement. And that’s, that’s sad, you know, so we have to start yeah we have to start there. And as far as the flashlight I mean I truly believe people are walking with whatever light they have in front of them, you know I called it a circle of light, and the people that are not comfortable moving out of that circle of light will find other people that have the same exact vision that they do and they’ll stay with them and other people. The interfaith people or they may each have their own circle of light when they walk together the whole field of vision grows. And you can see more and you can walk easier together. And so that’s, that’s what we need to do is share our vision of life with others and and hope that they find it interesting and say oh that looks kind of cool, I want to learn more about that. But you can’t teach people with words, it has to be with actions.

Yes. It’s a beautiful vision because there you can kind of see the end of the movie with all the flashlights kind of lighting the entire field in a way, just, it just takes the humility and like you said right at the very beginning that kind of childlike longing to know more from the one who has something you never saw before.

Yes.

Robyn thanks a lot we overcame a lot on the tech side to make it and it’s been very enriching for me I hope, I hope you felt the chance to get some of your thoughts across, and I hope we have a chance to do this again.

Yes, I really enjoyed it, and you know my whole purpose is to try and help people, giving them, the seeds and the pearls that I’ve found that will help them along their path, you know we all have to walk our spiritual paths alone we have to learn ourselves but we can help each other along the way.

Beautiful, beautiful. Thanks a lot, Robyn. Have a blessed day.

Thank you. You too.

Comments

Interview with Interfaith Veteran, Robyn LeBron-Anders: “Do You Think We Will Ever Get It Right?” — No Comments

HTML tags allowed in your comment: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>